When the collodion process was popular and new, only those who made negatives and prints were called "Photographers." Tintypes were made by "Tintypists" or "Ferro-typists", ambrotypes by "Ambrotypists," etc, and were not considered to be as serious. While there was undoubtedly a higher degree of skill required to produce negatives, the term "Photographer" also implied ownership of a brick and mortar studio where customers could return to, to pick up their prints, while tintypists were often itinerants moving from town to town.

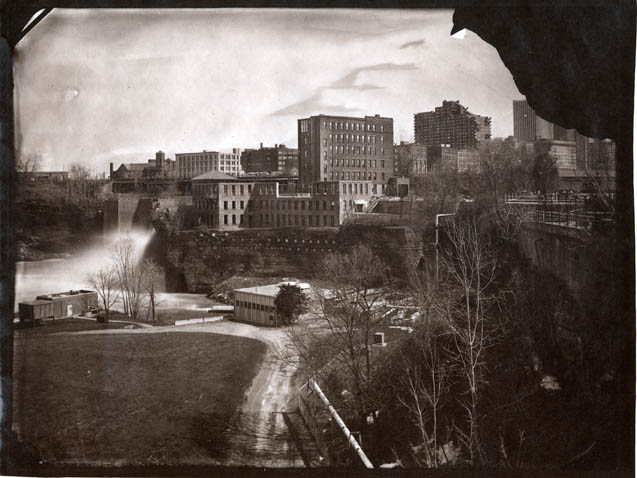

There were exceptions like Julia Margaret Cameron and Oscar Rejlander, but the vast majority of photographers of the period strove for "perfect" reproduction from life. Collodion is blue/UV sensitive but insensitive to many other colors. To counteract the relative insensitivity to warm skin tones, the faces on most portrait negatives were retouched. In addition, skies were often "painted out" on negatives to disguise artifacts that are emphasized in areas of one tonality. The negative for the image taken of Rochester High Falls was damaged. While retouching the negative "artistic license" was taken, removing some of the buildings. In addition, dramatic clouds have been added by drawing on the tissue overlay used during printing.

In addition to the tactile and visual qualities inherent in making collodion images, artists and photographers are drawn to the process for two reasons, which appear to be completely opposing sensibilities.

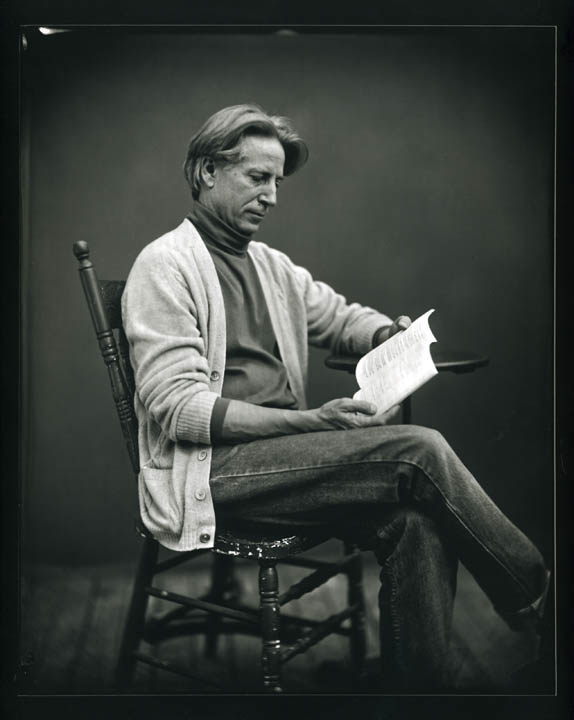

Many artists are initially seduced by the streaks, swirls, and markings inherent in the process. Whether produced intentionally or by indelicate handling, these honest artifacts can contribute to the image in a way that is often copied, but impossible to achieve by any other means. In rare cases, these artifacts can be found in 19th c. examples, (as seen in the previous image, W.M. Rossetti, 1865, by Julia Margaret Cameron); though more often they are visible in contemporary work.

There is a dark side, however; a little goes a long way. Like all visual arts, the technique is not the only facet of art making, the flaws of any process, no matter how interesting, are usually secondary to the artistic concept. Sometimes they are intentional, in many cases they are the residues left by those who have not yet mastered the process.

Less realized today are the more subtle aspects of the collodion process. In the hands of the skillful, collodion is not a primitive product, but a sophisticated film without compromise. It is as primitive or as sophisticated as the skills of the maker. Virtually grainless images can be made on glass, making them finer and far superior to any other negative process.

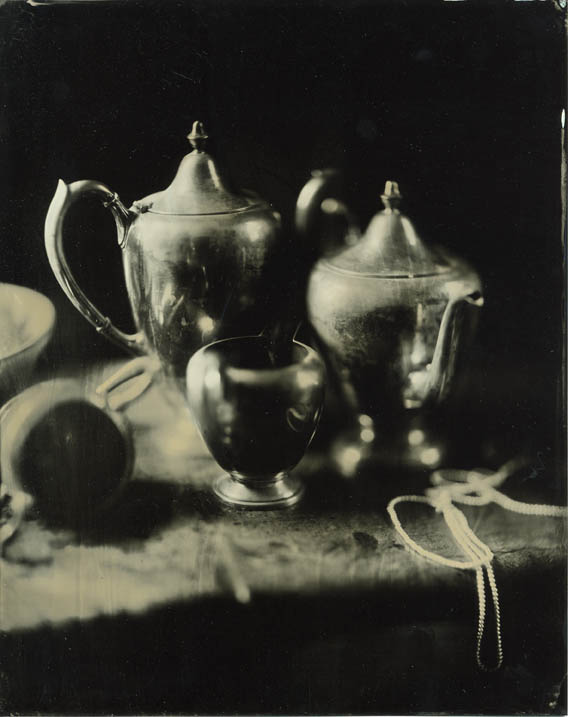

Were that not enough, collodion is also extremely versatile. Variants of the wet-plate process can be used to make one-of-a-kind positives on blackened metal, called "tintypes," or on glass, called "ambrotypes." Other collodion positives on glass are transparencies (or slides), milk glass positives, and orotones —all of which are second-generation images made from negatives.

A wide variety of supports can be used, such as colored and white glass, gold backings, and even thin sheets of mica. Dry pigments can be applied (as illustrated in Mark Osterman’s Ballyhoo, 2003) combined with burnishing or polishing the silver particles, adding yet another dimension to the image. It seems the uses for collodion are only limited by the imagination.

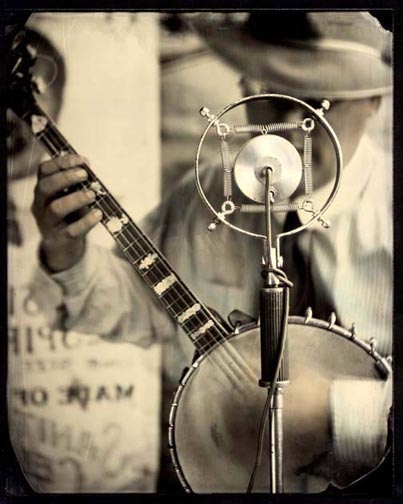

Today it is artists who primarily use the process. A relatively small number of specialists make collodion commercial portraits at living history reenactments as well. Typically both groups make tintypes or ambrotypes (in camera or using an enlarger), with a smaller percentage making negatives for enlarging.

NEXT: Modern Times

PREV: Developing the Plate